Gatekeeping is one of the great sins of online life. It means something like “to exclude someone from a discussion.” But we exclude people from discussions all the time. So why is gatekeeping bad?

***

In its online usage, “Gatekeeping” seems to have emerged in fan communities. In particular, it seems to have been used to describe (usually male) fans of a franchise excluding (usually female) fans by imposing arbitrary knowledge requirements. Per Urban Dictionary:

When someone takes it upon themselves to decide who does or does not have access or rights to a community or identity.

Consider the example:

"Oh man, I love Harry Potter. I am such a geek!"

"Hardly. Talk to me when you're into theoretical physics."

The idea is that “geek” is a community or identity, and taking it upon oneself to decide that “loving Harry Potter” is insufficient to join that community or identity is wrong.

Other pieces on gatekeeping are similar: Gatekeeping in gaming (Who is a real “gamer”?), the effect of TikTok on gatekeeping, whether teenage girls are cultural gatekeepers, gatekeepers who decide what food is disgusting. There’s even a large subreddit for documenting examples (though note that most of the examples are people getting mad about jokes).

From Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal by Zach Weinersmith

In the context of these online communities, “gatekeeping” seems quite annoying! Fan communities exist for mutual enjoyment of a hobby; they are not truth seeking in nature. Gatekeeping, in this sense and context, is discriminatory, and it’s silly because being a fan of something doesn’t and shouldn’t require memorizing arcane knowledge about that thing; it’s probably fine to let Harry Potter fans into the geek community.

What’s weird is that this usage hasn’t been kept to fan communities. It’s leaked into broader intellectual discourse, so much so that it’s beginning to completely confuse other debates.

And it’s making discussions insane.

***

Think of it this way: We all believe gatekeeping is good in a trivial sense. If someone was hurling insults and spewing meaningless claims, we would prefer they be excluded from discussion. In important or high stakes discussions, we might even think we have a duty to exclude them from discussion.

So we approve of gatekeeping.

That seems unfair: not all exclusion is gatekeeping. But that’s sort of my point: When you pack “to unjustly exclude” into the definition, you hide all the interesting claims you’re making. What is just exclusion?

My position is that the norms and questions around who should be allowed to participate in which discussion are highly complex and situational. They demand to be constantly negotiated. “Gatekeeping,” is a crude concept that serves only to confuse these debates rather than clarify them.

***

Or consider it this way: Expertise has some merit in discussion. We all agree on this. This expertise might be captured in their credentials, like their degrees or publications, but those are only proxies. (Clearly an expert who is dismissed for their lack of credentials is dismissed wrongly.) Experts are people who actually know something about the subject at hand. Depending on the nature of the subject, we prefer to keep the discussion more closed to experts, in the true sense of the word.

Austere debates in math and science are obvious examples: when a non-expert, who does not understand the subject, disagrees with an expert, they are usually “not even wrong” as they do not even have the requisite understanding to disagree. Even if they understood enough to argue, disagreeing with an epistemically superior—who is both better informed and better at aggregating information than you—is a hallmark sign of irrationality in the philosophy of disagreement: Why should you believe yourself over someone you know to know more and reason better than you?

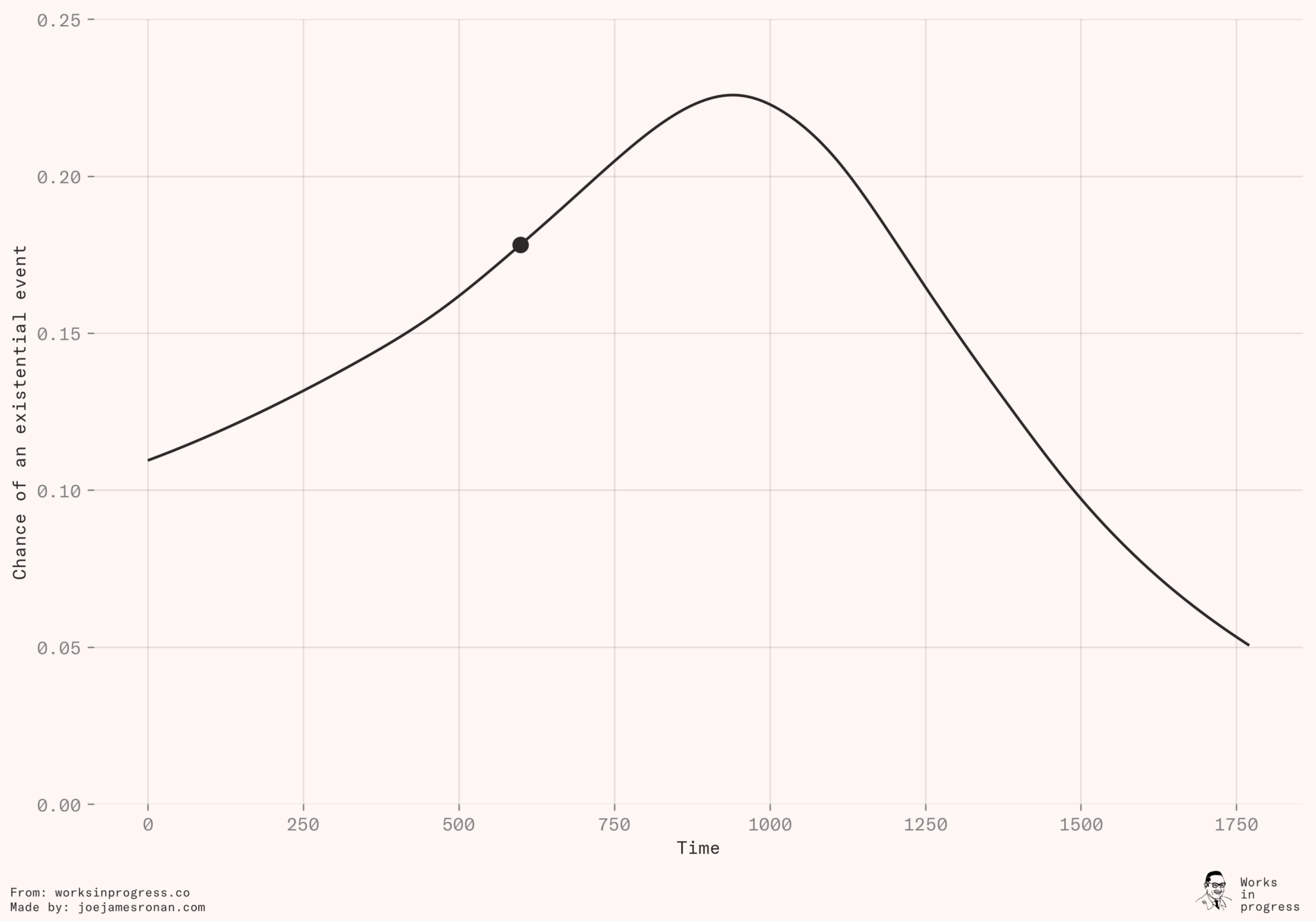

Math and science are too clear cut. Here’s a messier example: Consider the refrain during the early invasion of Ukraine: “Name the 11 countries that border Ukraine”—the implicit claim being that people who couldn’t name the bordering countries didn’t deserve to opine on the invasion.

From r/gatekeeping

Is this a good discussion norm? I’m not sure–It seems like a bit of a gotcha question. Should one be forgiven for forgetting Moldova?

But it’s at least plausible that someone’s opinion on geopolitical conflict who doesn’t have any knowledge of a region is as bad as someone with no mathematical understanding trying to argue about complex equations. It’s easy to imagine instances where we would ask someone to not comment on a country’s affairs if they didn’t know basic facts about it. The question is simply: which facts?

It’s not clear cut. But these debates—on what knowledge is requisite to participate in a debate—are the only way we can figure it out. Blanket bans on gatekeeping teach us nothing, and just make the discussion worse.

***

Another strange aspect of the gatekeeping debate is how closely it runs parallel to a debate about the value of experts. “Follow the experts,” we are told on COVID, usually rightly once the normal scientific process has sorted itself out. Certainly there might be specific failure points–reasonable people may differ on the best way to identify these failures–but nobody really believes that whether MRNA vaccines work is up for debate.

We have more intense forms of pro-expert discourse: There’s a discussion of “epistemic trespassing,” the briefly loved and now mostly reviled philosophical term. Or isn’t Annie Lowry’s Fact Man the great enemy of the gatekeepers?

So which is it? Should we do more to protect the status of experts? Or should we strike down the gatekeepers? Again, the “Don’t gatekeep” maxim teaches us little.

There’s an analogous debate around “platforming.” Many–especially those who object to gatekeeping–often suggest that media platforms should ban or censor certain people due to their alleged harmful effects. Once again, we all believe in gatekeeping.

***

When we recognize this, we can discuss gatekeeping in the abstract as morally neutral. Some people might support more of it, some less, and all will disagree on when it should be used. But the notion that nobody should ever gatekeep would be seen as strange.

This would be consistent with the first usage of “gatekeeping,” in a paper on food habits [1]:

Entering or not entering a channel and moving from one section of a channel to another is affected by a “gatekeeper.” For instance, in determining the food that enters the channel “buying” we should know whether the husband, the wife, or the maid does the buying. If it is the housewife, then the psychology of the housewife should be studied, especially her attitudes and behavior in the buying situation.

Understanding who the gatekeeper was and what motivated them could help one to understand why some families ate certain foods and others didn’t. But the act of gatekeeping is implicitly understood as normal and inevitable. It was the consequences of that gatekeeping were up for debate. It’s a small switch that would make some debates infinitely less mind numbing.

***

One still might suspect that gatekeeping is more deeply wrong [2].

You could argue that using Philip Tetlock’s research: Experts are very bad at making predictions. Our best forecasters are much better. This was recently confirmed in a meta-analysis from the new research consultancy, Arb. So gatekeeping is bad because (even true) experts are overrated.

But the argument doesn’t really work: If expertise is good for some things and poor for others, it’s worth trying to figure that out. But answering them will only help us be better gatekeepers. We might figure out that we should always exclude experts when making predictions, and instead only allow well-calibrated forecasters through our gates.

Or perhaps you believe in competitive markets: Always give people more options, and let consumer choice sort it out. So more voices are always better in the market for ideas. There’s a lot of reasons one might object to this point–it assumes an awfully competitive market for truth, and potentially the problem of choice fatigue–but there’s a more fundamental problem: gatekeepers themselves are competing. Some groups and communities will have very little curation in their discussions and some have a lot. Consumers choose which they prefer. One can’t object to gatekeeping for competition’s sake, because gatekeeping is one of the dimension on which communities are competing.

***

All that is just to say: It’s time to stop worrying about gatekeeping and start worrying about how to be a good gatekeeper.

[1] I don’t believe that etymology has a special linguistic significance. I just note it here as a point of comparison.

[2] In a funny way, the position sort of horse shoes around to something like “free speech absolutism”